A Naive Framework For Understanding Change

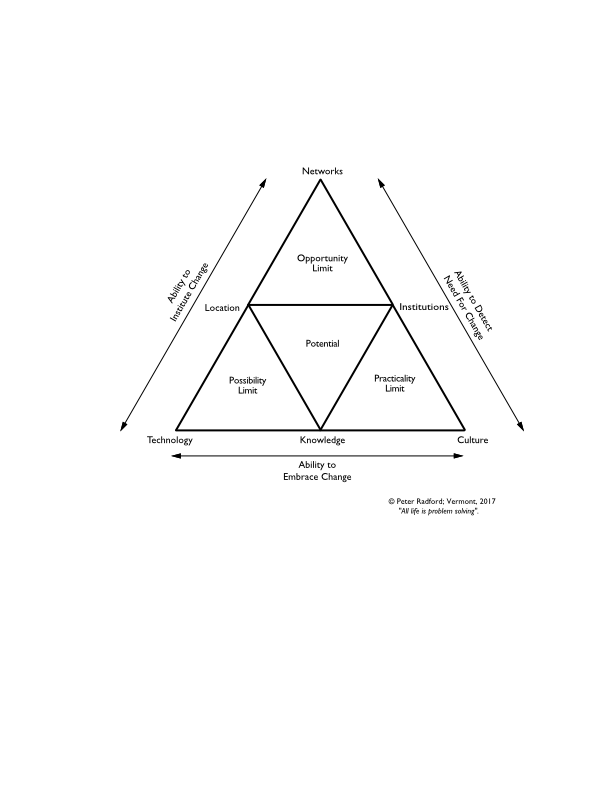

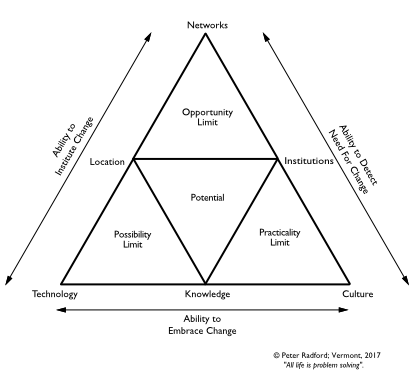

A few days ago I added a copy of a framework I use to the end of an article. Some of you have asked for a brief discussion of it. So here it is again:

The purpose of this simple framework is to make us consider all the aspects of an economy that affect growth, especially during times of change. It began, like a lot of the things I do, as a checklist to go through whilst building business strategies, but I have also used it in the context of explanations for economic growth.

The central point is that economic potential is limited by certain factors, but is also accelerated by others. The relationships between those inhibiting and those encouraging growth and/or change determine what happens. You cannot build a theory of growth without examining the tension that exists amongst all these factors.

So, for instance, what I call “Locale” is a very broad category that includes access to natural resources, access to lines of communication, geographical size, and other physical phenomenon. This is hardly revolutionary, but it is sometimes overlooked. It also would include access to and uses of sources of energy, which to me is a ‘factor of production’ far more fundamental than any of those used in traditional economics. Call me naive, but absence of energy makes the study various combinations of capital and labor a far less interesting or relevant discussion.

Speaking of factors of production that make sense, by “Knowledge” I mean the base of propositional knowledge that exists within the society whose economy we are looking at. I realize that basic science is oftentimes a laggard behind the use of some form of technology — the steam engine is the iconic example of this, the scientific explanation of steam power lagged well behind the initial use of steam in industry — but the entire corpus of propositional knowledge ultimately is the arbiter of a society’s long term opportunity to create prosperity. With the definition of prosperity being elastic enough to include living standards as well as material standards.

The “Institutional” constraint is well discussed, but is also very often overlooked in standard growth analysis. The concept of an ‘institution’ is a very broad one indeed, and drawing a line between culture and institution can often be arbitrary. Nonetheless I see institutions as the ‘baked in’ version of past decisions on how a society wants to channel behavior. So the legal system, and in the context of growth especially things like property rights, are vital either as constraints or accelerants of growth. So too are other institutions such as the political system, various religious entities, and the whole host of others that fill libraries of analysis. For our purposes we can be naive and accept that in any society there is a prejudice towards or against growth in its institutional arrangements.

Taken together, then, these three categories — Locale, Knowledge, and Institutions — set a limit on the potential a society can open up for itself. Obviously this needs modification because there other significant factors that come into play, such as the aforementioned cultural and technological influences that modify how a society can access its potential.

I identify three such additional factors:

“Culture” is very much a topic of discussion at the moment. There have been a number of books recently talking about the role of cultural shifts as a foundational aspect of modern growth. I would agree with this idea. The most important aspect of culture that we need to take into account is oftentimes overlooked: it is the social acceptance that change is both possible and/or desirable. Attitudes in our modern era stand in stark contrast to the resignation, fatalism, and outright rejection of the possibility or desirability of change in prior eras. Even today in some parts of the world the older cultural opposition to change and growth place severe limits on the practical access of potential in those areas. A culture that accommodates and welcomes change is one more likely to experience a rise in prosperity, so it plays a significant role in our overall framework.

Next, obviously, is “Technology”. It constantly amazes me that it took mainstream economics so long to account for technology as a driver of growth. This despite all that had been written and all the very evident change going on within the economy. I simply treat this prolonged oversight as an example of how the methodological myopia of a discipline can constrain its ability to develop ideas that, to an outsider not so constrained, can appear obvious. In any case: technology — what we can call ‘prescriptive’ knowledge — is a primary agent in making what is potential a true possibility. By this I mean that technology makes actually possible things that previously were simply theoretically possible.

Finally, in this very brief tour of my naive framework, I have “Networks”. This is also often overlooked. By networks I mean all the various physical, logical, and social ways that information, norms, cultural attitudes, energy, materials and so on can be moved around. Networks place a great limit on the opportunity to access potential: there is no advantage in having great natural resources if they are locked away in some inaccessible location. Nor is there much opportunity for a child who grows up without access to the advantages of a good education or who is precluded form such access by lack of social standing or physical transportation. Under this heading we can also discuss the relative centralization of decentralization of control within an economy, and the relative openness of the power structures of society to novelty.

So this is my framework. I don’t claim it as anything other than a way of articulating my thoughts about growth, its desirability and likelihood.

It is naive. But then again, as I have argued before, so is all economics.