Seven Out Of Ten

Seven out of ten isn’t a bad score. It isn’t great either. It’s a majority, but isn’t totality.

What am I talking about?

I came across the reference to seven out of ten in Paul Krugman’s column this morning, and it’s worth pondering.

Let me set the scene:

One of the current most widely used criticisms of more stimulus for the economy – it could use the help – is that governments never get rid of the so-called ‘temporary’ measures once the emergency has passed. All that happens is that the programs designed to bolster the economy get baked into an ever growing pile of permanent government spending.This is not true. In fact it is way wide of the mark.

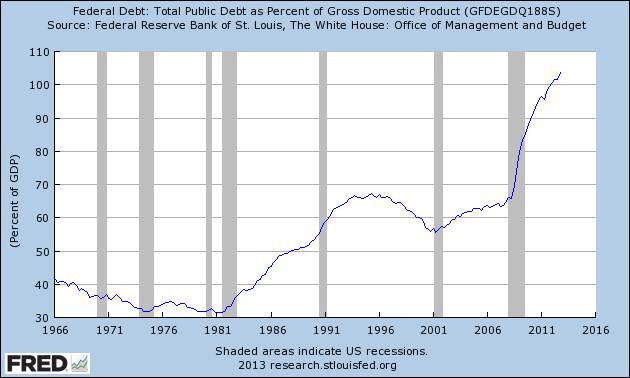

The best way to look at government spending is not in absolute dollars, but in the ratio of spending to GDP. With an ever growing population and an economy growing through time, the level of actual dollars spent is always going to rise. The crucial point is to see whether the portion of the economy designated as government spending is rising faster or slower than the whole.

And this is where seven in ten comes in.

Of the ten post World War II presidents before Obama seven have left office with government spending lower as a percentage of the economy than it was when they entered office. So we have only three fiscal laggards in the last seventy of so years. Three rotten apples who expanded government, and coincidentally, added to our national debt more than the others.

They were Ronald Reagan, and both the George Bush’s. Three rotten apples. Three Republicans. Three fiscal calamities.

This is not what you hear from right wingers of course.

Poor old Ronald Reagan, we are told, had to deal with those high interest rates. Remember those? Paul Volcker went after inflation by raising rates and plunging the economy into a severe recession in 1980/81. The downturn was nasty. The recovery pretty good. And that explains Reagan’s pile of debt. Well not really. Reagan’s pile of debt came from his refusal to pay for his defense build up by raising taxes. Instead he borrowed the money. He thus earned his place in history as one of the few, very few, US presidents to expand the national debt during a period of non-emergency.

The key point to bear in mind about Reagan is that he might have been many things: he might have talked a good game, and he might well have been the originator of our current vogue of ‘blame the government’, but he was not, by any stretch of the imagination, a small government guy. No not at all. He expanded big government. Despite his rhetoric. And despite the efforts of his subsequent sycophants who toil endlessly to cover over the traces of his fiscal follies.

Then there was George I. No one seems to talk about him much any more. Probably for good reason. Go ahead: try to recall anything about him. Suffice to say he continued the Reagan trend, only with less brio.

And then we come to the true classic: George II. If ever anyone ought claim the title to fiscal recklessness George II is he.

Dear George II has left such a trail of wanton wreckage that we almost forget the horror that was his fiscal policy. He inherited a Federal budget under control and generating a small surplus, along with a government spending level on a downward track, and promptly blew it all up. The political headline was that if the Federal government budget is in surplus it must be taking in too much tax revenue. Therefore that surplus can be repaid to taxpayers without jeopardizing the government’s fiscal position. The political reality was different: the goal was not to balance the books by returning a modest amount. It was to undermine the government by returning so much that the books were thrown into imbalance and a false need to cut spending thus created. After all, if you want to get to a smaller government what better way is there other than to defund it?

The problem was that George II was not good at math and, besides, was not truly an advocate of small government. One or two of his pet projects, notably one to do with Medicare, piled on the government spending, but since he had cut taxes and thus revenue, debt as a share of the economy rose, not fell, during George’s rein.

Naturally we are told by George II’s defenders – yes there are some – that his errors are really those he inherited from Clinton, and that the expansion of government during those long eight years was simply a function of Clintonian policies having a long incubation before they did their damage.

Sorry that won’t work. The Medicare Prescription Drug, Improvement, and Modernization Act of December 2003, which added about $530 billion to government spending, was not a Clinton era policy. It was the biggest revamp of Medicare since its inception, and included an infamous prohibition preventing the government from negotiating lower drug costs with the pharmaceutical industry.

So there you have it. The three rotten apples of fiscal imprudence all turn out to be Republicans. The clear message seems to be that if you want to expand government debt, elect Republicans. This is not exactly what you read about in the press is it?

Yes that’s right. The party currently venting its spleen over the need for tighter budgets and the dangers of debt is the very party that blazed the trail for increasing debt. It has, at least in terms of the post-war era, a long and hallowed tradition of inflating the debt, and fiscal recklessness.

Anyway, in case you think I am misleading you, here’s the chart: